WARNING: THIS POST IS BANDWIDTH HEAVY

Wake to Extinction was a collaboration with 350 Tacoma‘s Art Activists and Arts Bridging Communities, combining grief precessions and artmaking featuring giant illuminated insect lanterns, and the projected imagery created by participants of Extreme Makeover with Beverly Naidus from the University of Washington.

As we mourn the loss of life in this 6th Mass Extinction, we also dare to imagine building a beautiful future for the Puyallup Estuary. We make art honoring the endangered and the deceased, we sing to acknowledge and heal our hearts, we imagine destroyed ecosystems revived, and we walk. We walk a lot. Because grief is felt and processed in our bodies, and that’s part of why we hit the streets.

I signed on near the beginning of the project in May of 2019, new to 350 and agreeing to take a 3-day lantern making workshop with Sarah Lovett, the sculpture artist 350 hired, in order to learn how to make the bugs, disseminate and streamline the process, and then teach the method to 350’s volunteers.

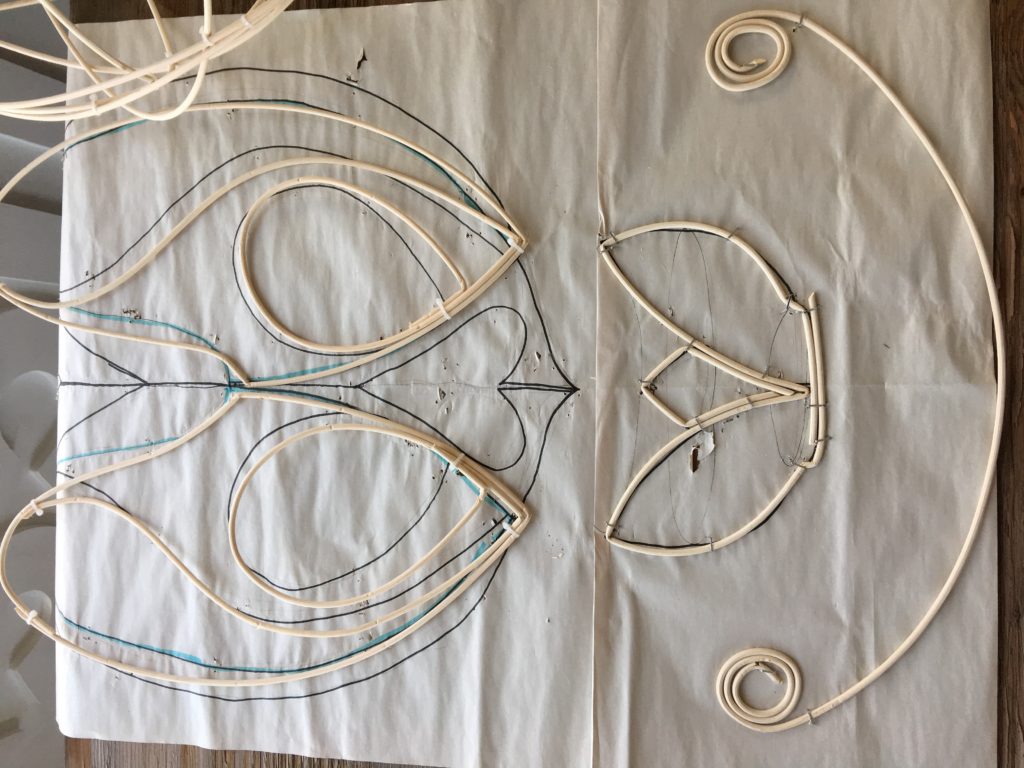

The method involves research and drawing the facade of the bug, tracing designs onto newsprint, soaking and molding wet reed into two-dimensional shapes stapled onto plywood, creating a three-dimensional frame by adding dry loops of reed to the dried 2-D panels, then coating the skeleton first in cheesecloth, then in paper mache, then in decorative tissue. For starters.

I also ended up becoming the meeting facilitator, the precession planner/stage manager, and the Master of Ceremonies, in addition to my original commitment to this event. It was an intense few months.

STEP 1: INSPIRATION AND DESIGN

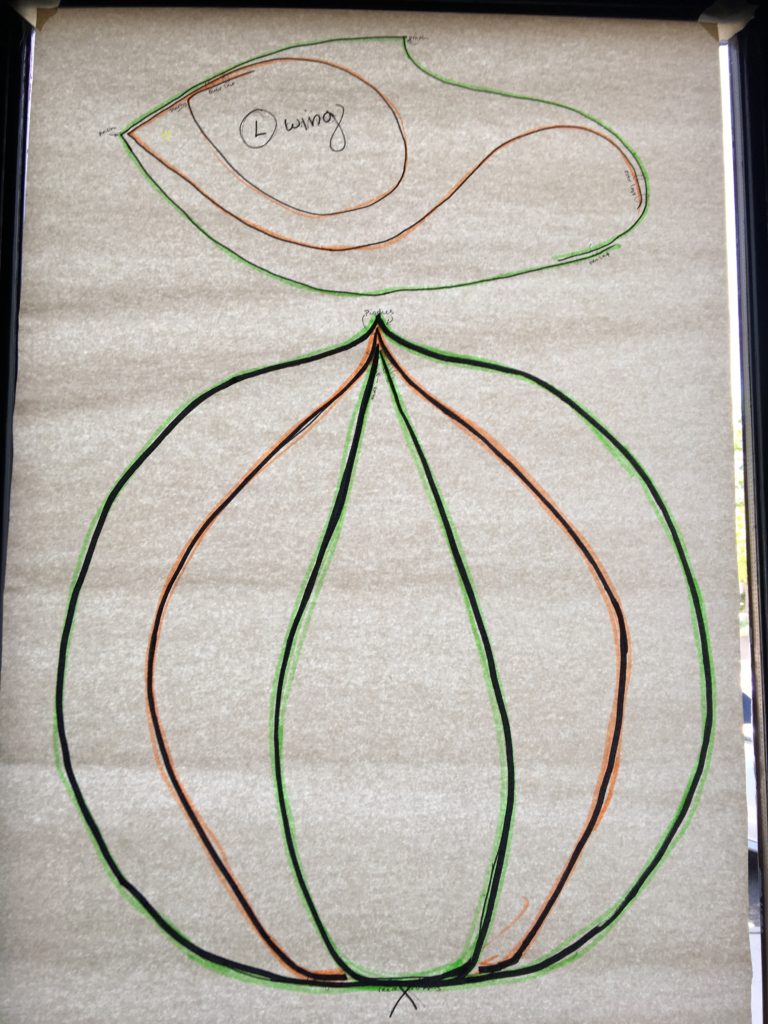

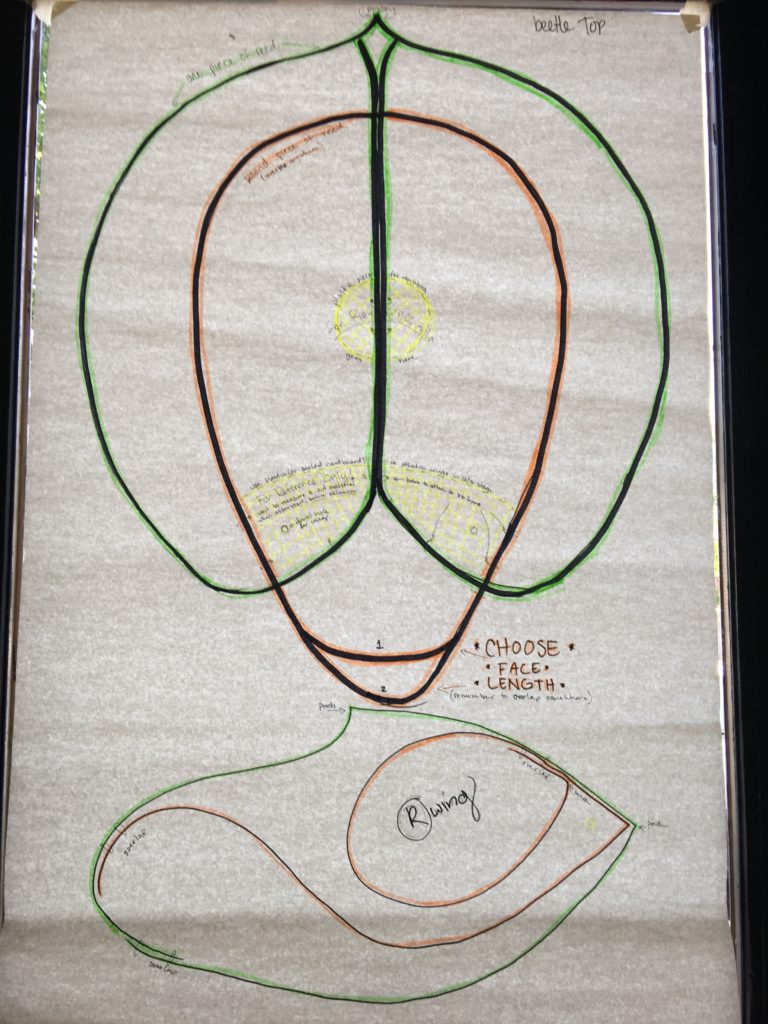

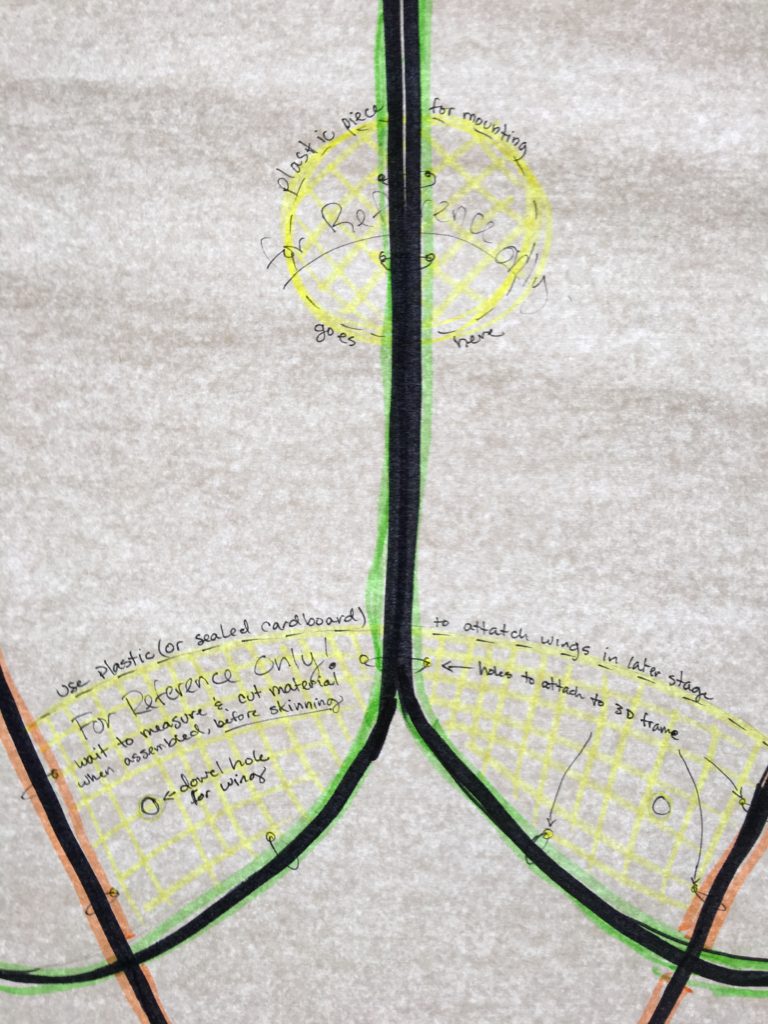

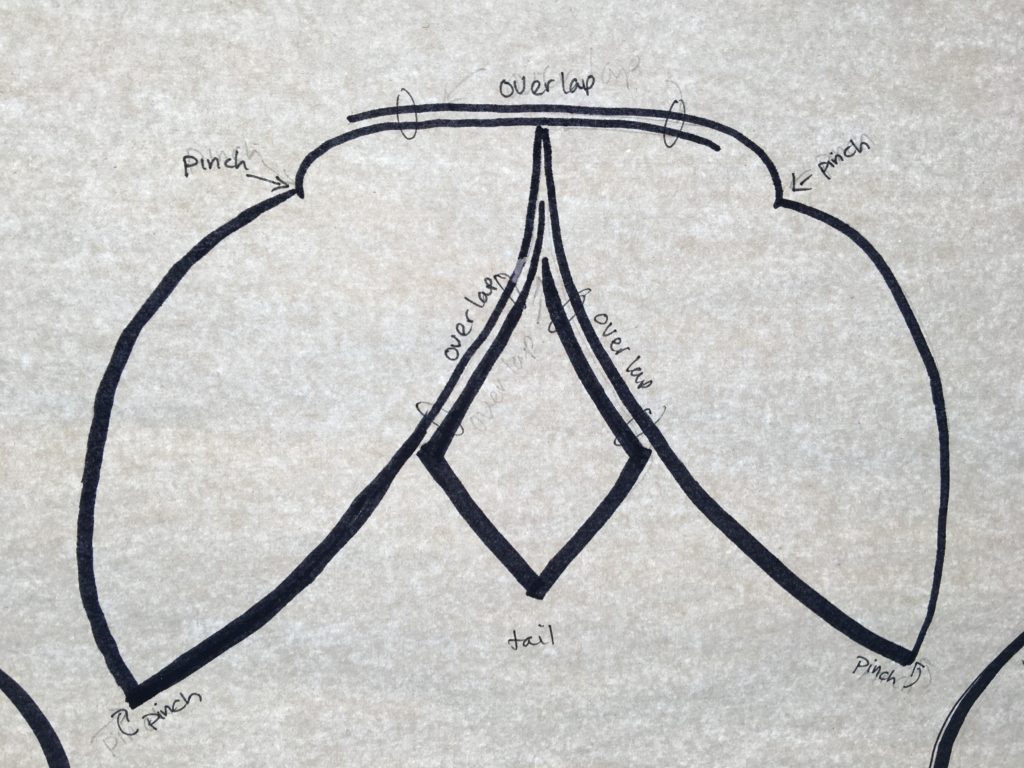

The first stage of bugmaking was design, which includes research and drawing that I won’t get into here; but after completing the initial workshop and learning a few important details about the rest of the process, I created a new version of my initial drawing for the imaginary beetle I created, including some references for future stages; like mounting the sucker somehow, and designing the drawing so it would be discernible by someone who hadn’t already designed it.

By far the most difficult aspect of designing these things was wrapping my head around how 2-d panel drawings were going to shape out to be three dimensional. It was impossible for me to think about where a cardboard tube might be mounted in order to put a lantern on a pole without the experience of having built the thing already.

I worked my way through it by experimenting and deviating greatly from the first drawing I used, but those are the details that are ideally thought about beforehand, if anything to save the effort and time it takes to create spare parts after the fact.

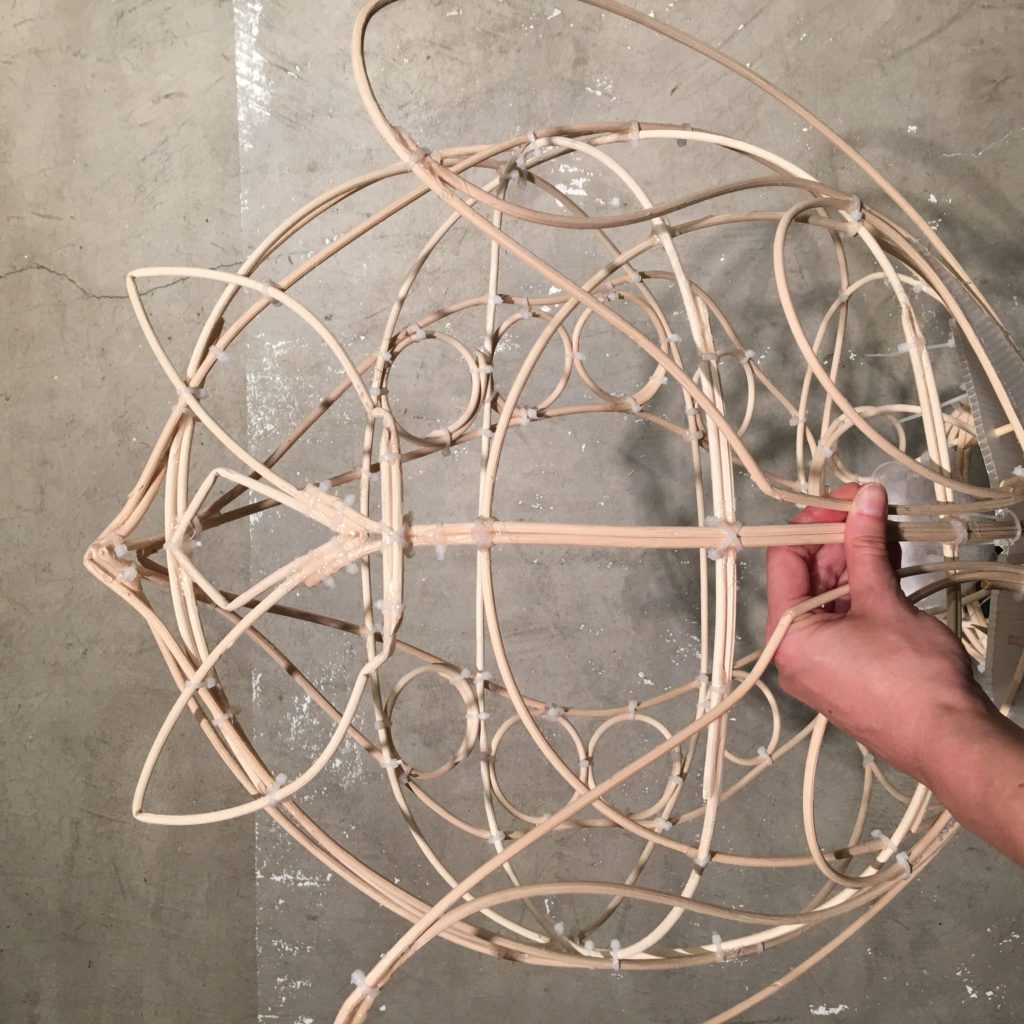

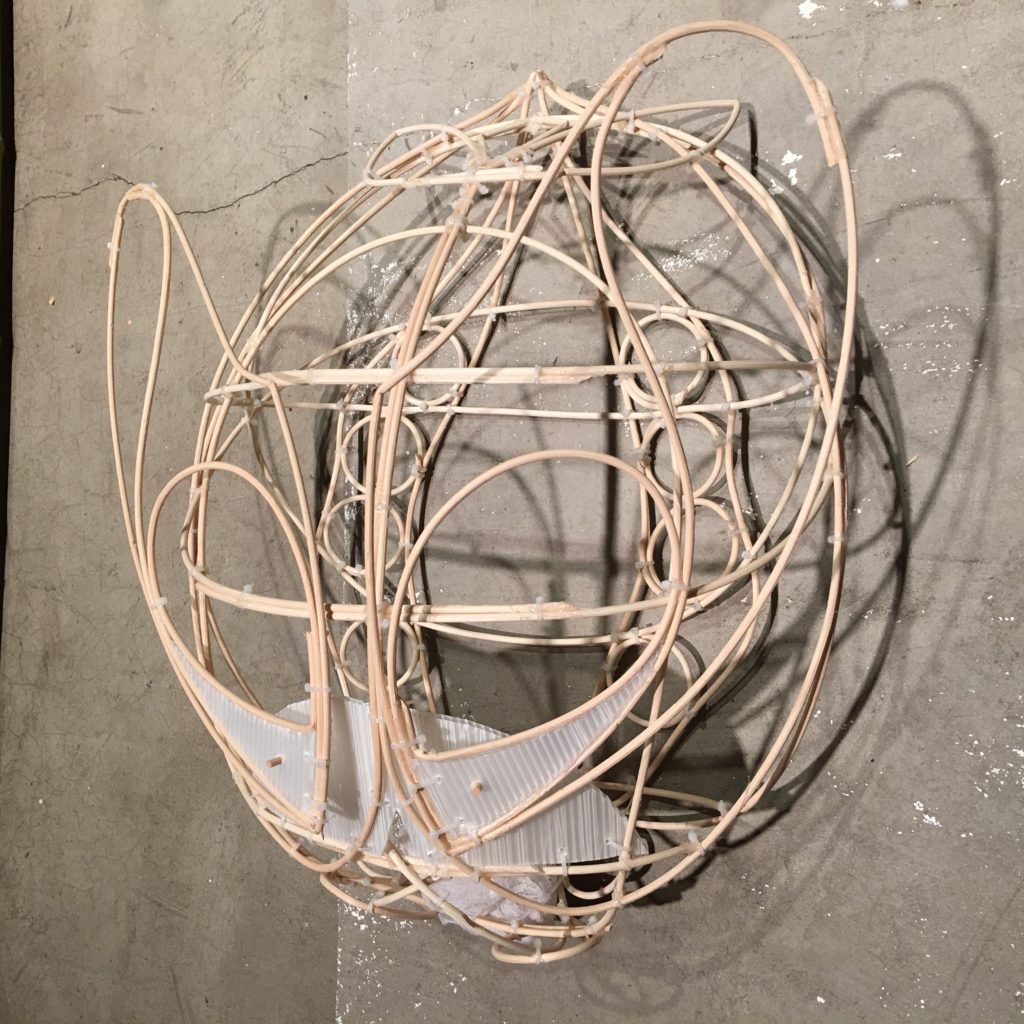

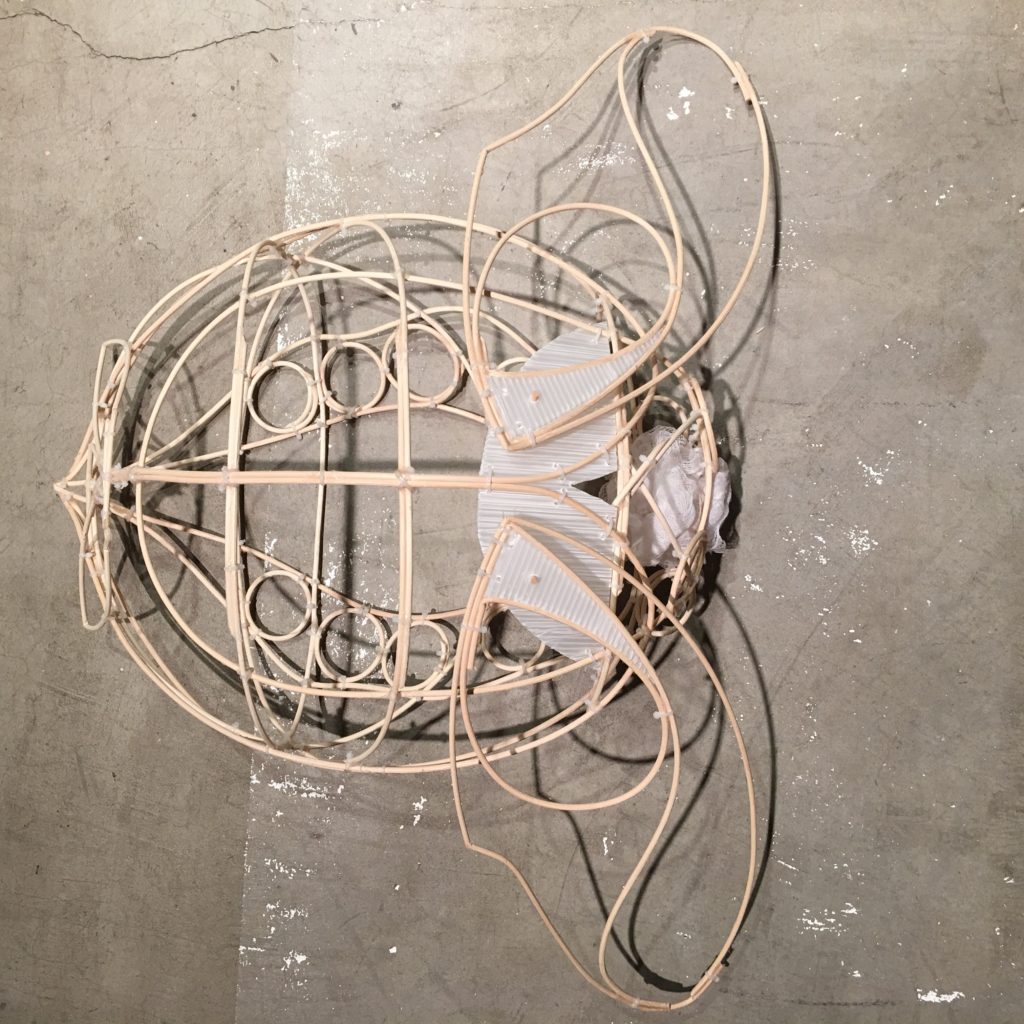

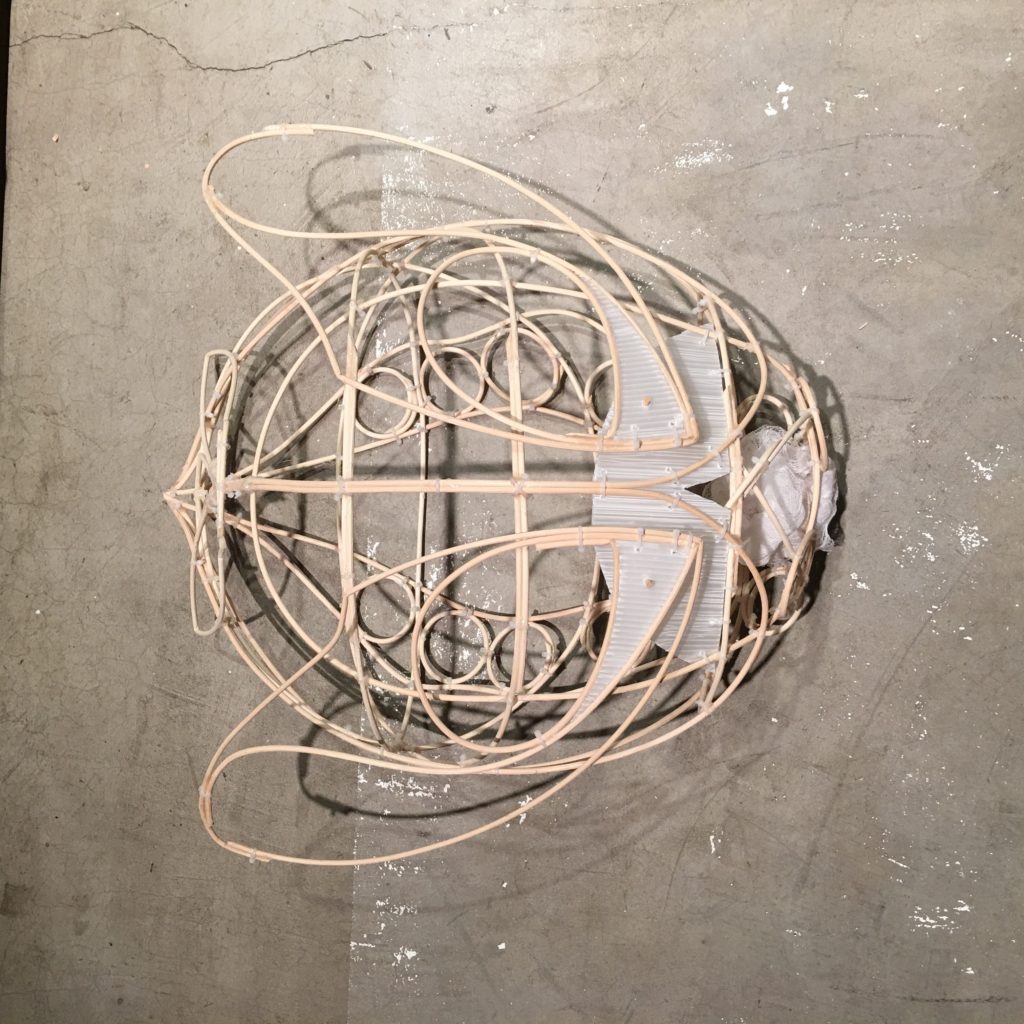

STAGE 2: BONES

The next stage of bug creation meant turning flat sorta-parts for a sorta maybe bug thing into a 3-dimensional object. Many zip ties, finger pinching, jaw clenching and much glue gunning were utilized during this stage of the process, which I am pretty sure was the one I hated the most.

It was here, however, when I began to understand other design elements, like attachments, and mounting, and figured out that I better make leg holes to attach something to.. which, haha, you guessed it – I didn’t actually end up using.

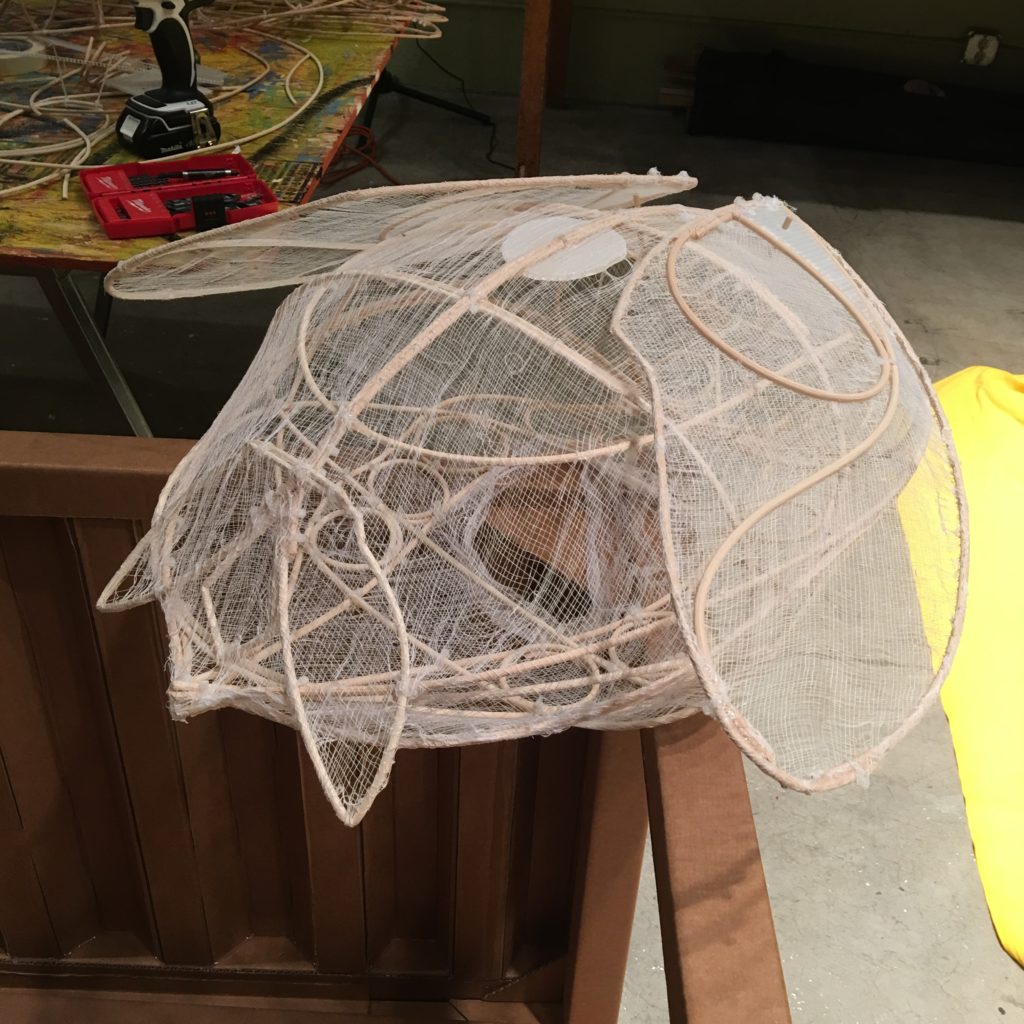

STAGE 3: SKINNING

Once the skeleton is achieved it’s time to start fleshing out, and the first layer is cheesecloth. This is a lightweight breathable material that creates an under-layer for wet paper to cling to in the next step of skinning. Again the glue gun earned its keep, as the cheesecloth is adhered to every intersecting spine of reed in order to gain the taut required to be a good underskin.

To give a reference for the amount of time these lanterns took; the original workshop was set to be 15 hours over 3 days, with the expectation that everyone would have a bug finished by the end of it. We went about 2 hours over time every day, and this cheesecloth phase is how far I had gotten in that amount of time.

STAGE 4: DECORATING

The decorating phase was bittersweet for me in this project. As part of my initial role as a bugmaking facilitator, it was my job to think of time-saving ideas, and that was a tall order for a medium this intensive and involved. But I came up with a brilliant one, I thought: Ghost bugs. But they were decided against, and I’m still a little salty about it truth be told.

The legs were finished in black paper mache, and affixed with zip ties and hot glue. Once the skin is dry, it’s possible to cut and puncture to attach peripherals, or to cut flaps for access inside to install and turn on/off lights.

I ended up cutting jigs out of newsprint to trace the shapes I wanted to create along the spines of the beetles skeleton showing through. Since I had a polkadot pattern, an asymmetrical creature, had to work with large pieces of very delicate paper to maintain that pattern, and wanted cleanish edges, it was the only way I could think of to accomplish what I wanted.

I covered the face in the same silk scarf as the wings, which I ended up glueing on rather than attempting to mess with articulation (or having to man an articulated insect in the parade), and used reclaimed plastic for the eyes (not pictured).

Here’s a good silly video of my little dead goth beetle, all finished up with legs and wings and everything, ready to help us mourn the first mass extermination.

As for the actual event; we ended up abandoning a fair bit of the intensive planning work that had been done when it was decided the night before that we best move indoors due to weather.

This was a labored but absolutely correct choice, and the experience we were able to provide under shelter with just one last sprint of the chaotic flexibility that was required of this creature from day 1 ended up creating a landing space for even more stuff that popped up; like our drummer backing out an hour before call, it being too cold and windy for an entirely outdoor event and 1.5 mile walk, plus the ability to offer food to our grievers.

All said and done, we hosted around 60 people throughout the night, beginning with hands uncurling and feet grounding in a group breathing exercise, continuing with singing beautiful call and response songs, witnessing and discussing slideshows of art created in the honoring of grief, with people coming out of their houses as we walked 12 blocks rather than 1.5 miles, and my favorite part of the event as it unfolded: the Eulogy, written and delivered by Reverend Barbara Turner, PhD.

Even as a space holder with a lot on my mind, I received a lot from this event myself. Seeing the 10 bugs we made lit and being stewarded by participants rather than builders mattered to me more than I expected, especially given that we originally wanted 50. They are fewer than that, but they are their own beings and they live with the intention and focus that so many volunteers and artists imbibed in them while they were built.

I also had a profound experience exploring my English heritage through dressing for this event. Claiming it and signaling it outwardly in an intentional way I have never done, I took away some Big Things regarding the limitations of a culture – my culture *gulp*- that so glamorizes only small superficial elements of grief, forcing a performance spectacle that is expected to go on in perpetuity, and in public… but only if you’re seen as a woman. It caused me to consider the thread that weaves through my performances all the way back to Obsidian.

“We gather tonight and share in grief because this is the old food that gets turned into compost as it cooks through the winter, the nutrients in soil that will feed and inform the seeds of the future, the new systems that must be born if humanity is to survive in a decent way. A kind way.

Tonight is a night to turn our grief and anger and fears, maybe some guilt or regrets or a sense of hopelessness, turn all of that into that compost, together we use this to feed the seeds of a just future for all people. We grieve because it helps us wake.” -Rev. Barbara Turner, PhD